The original jupyter notebook is on my programming_notebook repository.

Classification

Supervised learning

Unsupervised learning: Uses unlabeled data

- Uncovering hidden patterns from unlabeled data

- Example:

- Grouping customers into distinct categories (Clustering)

Reinforcement learning

- Software agents interact with an environment

- Learn how to optimize their behavior

- Given a system of rewards and punishments

- Draws inspiration from behavioral psychology

- Applications

- Economics

- Genetics

- Game playing

- AlphaGo: First computer to defeat the world champion in Go

Supervised learning

- Predictor variables/features and a target variable

- Aim: Predict the target variable, given the predictor variables

- Classification: Target variable consists of categories

- Regression: Target variable is continuous

Naming conventions

- Features = predictor variables = independent variables

- Target variable = dependent variable = response variable

Supervised learning in Python

- We will use scikit-learn/sklearn

- Integrates well with the SciPy stack

- Other libraries

- TensorFlow

- keras

Exploratory data analysis

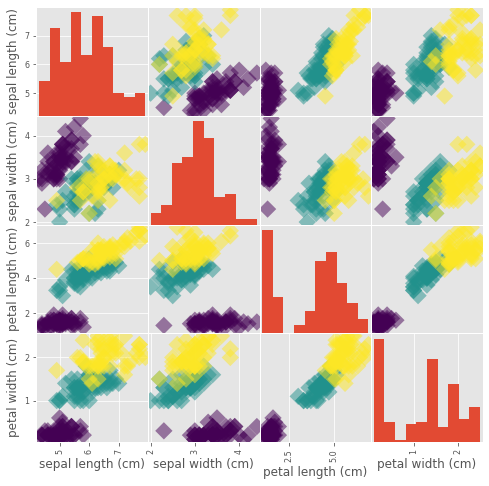

The Iris dataset

Features:

- Petal length

- Petal width

- Sepal length

- Sepal width

Target variable: Species:

- Versicolor

- Virginica

- Setosa

The Iris dataset in scikit-learn

from sklearn import datasets

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

plt.style.use('ggplot')

iris = datasets.load_iris()

type(iris)

sklearn.utils.Bunch

print(iris.keys())

dict_keys(['data', 'target', 'target_names', 'DESCR', 'feature_names', 'filename'])

type(iris.data), type(iris.target)

(numpy.ndarray, numpy.ndarray)

iris.data.shape

(150, 4)

iris.target_names

array(['setosa', 'versicolor', 'virginica'], dtype='<U10')

Exploratory data analysis (EDA)

X = iris.data

y = iris.target

df = pd.DataFrame(X, columns=iris.feature_names)

print(df.head())

sepal length (cm) sepal width (cm) petal length (cm) petal width (cm)

0 5.1 3.5 1.4 0.2

1 4.9 3.0 1.4 0.2

2 4.7 3.2 1.3 0.2

3 4.6 3.1 1.5 0.2

4 5.0 3.6 1.4 0.2

Visual EDA

_ = pd.plotting.scatter_matrix(df, c = y, figsize = [8, 8], s=150, marker = 'D')

The classification challenge

k-Nearest Neighbors

- Basic idea: Predict the label of a data point by

- Looking at the ‘k’ closest labeled data points

- Taking a majority vote

Scikit-learn fit and predict

- All machine learning models implemented as Python classes

- They implement the algorithms for learning and predicting

- Store the information learned from the data

- Training a model on the data = ‘�tting’ a model to the data

.fit()method- To predict the labels of new data:

.predict()method

Using scikit-learn to fit a classifier

from sklearn.neighbors import KNeighborsClassifier

knn = KNeighborsClassifier(n_neighbors=6)

knn.fit(iris['data'], iris['target'])

KNeighborsClassifier(algorithm='auto', leaf_size=30, metric='minkowski',

metric_params=None, n_jobs=None, n_neighbors=6, p=2,

weights='uniform')

iris['data'].shape

(150, 4)

iris['target'].shape # targets needs to be a single column with the same # of observation as the feature data

(150,)

Predicting on unlabeled data`

X_new = np.array(

[

[5.6, 2.8, 3.9, 1.1],

[5.7, 3.2, 3.8, 1.3],

[4.7, 3.2, 1.3, 0.2]

]) # feature in columns and observation in rows

prediction = knn.predict(X_new)

X_new.shape # 3 obsevation and 4 colums

(3, 4)

print('Prediction: {}'.format(prediction))

Prediction: [1 1 0]

Measuring model performance

Measuring model performance

- In classification, accuracy is a commonly used metric

- Accuracy = Fraction of correct predictions

- Which data should be used to compute accuracy?

-

How well will the model perform on new data?

- Could compute accuracy on data used to fit classifier

- NOT indicative of ability to generalize

- Split data into training and test set

- Fit/train the classifier on the training set

- Make predictions on test set

- Compare predictions with the known labels

Train/test split

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

# use train_test_split function to randomly split data

# firast argument is feature data, the second the targets or labels

# returns the training data, test data, training labels, test labels

# by default split the data into 75% training data and 25% test data, we specify the size using the test_size

# stratify=y:perform the split so that the split reflects the labels on your data, that is the labels to be distributed in train and test sets as they are in original dataset.

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size=0.3,

random_state=21, stratify=y)

knn = KNeighborsClassifier(n_neighbors=8)

knn.fit(X_train, y_train)

y_pred = knn.predict(X_test)

print("Test set predictions:")

print(y_pred)

Test set predictions:

[2 1 2 2 1 0 1 0 0 1 0 2 0 2 2 0 0 0 1 0 2 2 2 0 1 1 1 0 0 1 2 2 0 0 1 2 2

1 1 2 1 1 0 2 1]

# check out accuracy of the model

knn.score(X_test, y_test)

0.9555555555555556

Model complexity

- Larger k = smoother decision boundary = less complex model

- Smaller k = more complex model = can lead to overfitting

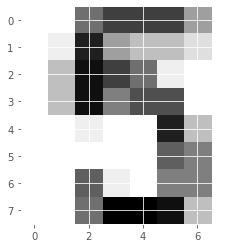

Exercise: The digits recognition dataset

# Import necessary modules

from sklearn import datasets

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Load the digits dataset: digits

digits = datasets.load_digits()

# Print the keys and DESCR of the dataset

print(digits.keys())

print(digits.DESCR)

# Print the shape of the images and data keys

print(digits.images.shape)

print(digits.data.shape)

# Display the 1011th image

plt.imshow(digits.images[1010], cmap=plt.cm.gray_r, interpolation='nearest')

plt.show()

dict_keys(['data', 'target', 'target_names', 'images', 'DESCR'])

.. _digits_dataset:

Optical recognition of handwritten digits dataset

--------------------------------------------------

**Data Set Characteristics:**

:Number of Instances: 5620

:Number of Attributes: 64

:Attribute Information: 8x8 image of integer pixels in the range 0..16.

:Missing Attribute Values: None

:Creator: E. Alpaydin (alpaydin '@' boun.edu.tr)

:Date: July; 1998

This is a copy of the test set of the UCI ML hand-written digits datasets

https://archive.ics.uci.edu/ml/datasets/Optical+Recognition+of+Handwritten+Digits

The data set contains images of hand-written digits: 10 classes where

each class refers to a digit.

Preprocessing programs made available by NIST were used to extract

normalized bitmaps of handwritten digits from a preprinted form. From a

total of 43 people, 30 contributed to the training set and different 13

to the test set. 32x32 bitmaps are divided into nonoverlapping blocks of

4x4 and the number of on pixels are counted in each block. This generates

an input matrix of 8x8 where each element is an integer in the range

0..16. This reduces dimensionality and gives invariance to small

distortions.

For info on NIST preprocessing routines, see M. D. Garris, J. L. Blue, G.

T. Candela, D. L. Dimmick, J. Geist, P. J. Grother, S. A. Janet, and C.

L. Wilson, NIST Form-Based Handprint Recognition System, NISTIR 5469,

1994.

.. topic:: References

- C. Kaynak (1995) Methods of Combining Multiple Classifiers and Their

Applications to Handwritten Digit Recognition, MSc Thesis, Institute of

Graduate Studies in Science and Engineering, Bogazici University.

- E. Alpaydin, C. Kaynak (1998) Cascading Classifiers, Kybernetika.

- Ken Tang and Ponnuthurai N. Suganthan and Xi Yao and A. Kai Qin.

Linear dimensionalityreduction using relevance weighted LDA. School of

Electrical and Electronic Engineering Nanyang Technological University.

2005.

- Claudio Gentile. A New Approximate Maximal Margin Classification

Algorithm. NIPS. 2000.

(1797, 8, 8)

(1797, 64)

Train/Test Split + Fit/Predict/Accuracy

# Import necessary modules

from sklearn.neighbors import KNeighborsClassifier

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

# Create feature and target arrays

X = digits.data

y = digits.target

# Split into training and test set

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size = 0.2, random_state=42, stratify=y)

# Create a k-NN classifier with 7 neighbors: knn

knn = KNeighborsClassifier(n_neighbors=7)

# Fit the classifier to the training data

knn.fit(X_train, y_train)

# Print the accuracy

print(knn.score(X_test, y_test))

0.9833333333333333

Overfitting and underfitting

In this exercise, you will compute and plot the training and testing accuracy scores for a variety of different neighbor values. By observing how the accuracy scores differ for the training and testing sets with different values of k, you will develop your intuition for overfitting and underfitting.

# Setup arrays to store train and test accuracies

neighbors = np.arange(1, 9)

train_accuracy = np.empty(len(neighbors))

test_accuracy = np.empty(len(neighbors))

# Loop over different values of k

for i, k in enumerate(neighbors):

# Setup a k-NN Classifier with k neighbors: knn

knn = KNeighborsClassifier(n_neighbors=k)

# Fit the classifier to the training data

knn.fit(X_train, y_train)

#Compute accuracy on the training set

train_accuracy[i] = knn.score(X_train, y_train)

#Compute accuracy on the testing set

test_accuracy[i] = knn.score(X_test, y_test)

# Generate plot

plt.title('k-NN: Varying Number of Neighbors')

plt.plot(neighbors, test_accuracy, label = 'Testing Accuracy')

plt.plot(neighbors, train_accuracy, label = 'Training Accuracy')

plt.legend()

plt.xlabel('Number of Neighbors')

plt.ylabel('Accuracy')

plt.show()

# It looks like the test accuracy is highest when using 3 and 5 neighbors.

# Using 8 neighbors or more seems to result in a simple model that underfits the data.

Regression

Introduction to regression

Boston housing data

from sklearn import datasets

boston_data = datasets.load_boston()

# change to dataframe

boston = pd.DataFrame(boston_data.data, columns=boston_data.feature_names)

boston['MEDV'] = pd.Series(boston_data.target)

print(boston.head())

CRIM ZN INDUS CHAS NOX RM AGE DIS RAD TAX \

0 0.00632 18.0 2.31 0.0 0.538 6.575 65.2 4.0900 1.0 296.0

1 0.02731 0.0 7.07 0.0 0.469 6.421 78.9 4.9671 2.0 242.0

2 0.02729 0.0 7.07 0.0 0.469 7.185 61.1 4.9671 2.0 242.0

3 0.03237 0.0 2.18 0.0 0.458 6.998 45.8 6.0622 3.0 222.0

4 0.06905 0.0 2.18 0.0 0.458 7.147 54.2 6.0622 3.0 222.0

PTRATIO B LSTAT MEDV

0 15.3 396.90 4.98 24.0

1 17.8 396.90 9.14 21.6

2 17.8 392.83 4.03 34.7

3 18.7 394.63 2.94 33.4

4 18.7 396.90 5.33 36.2

Creating feature and target arrays

X = boston.drop('MEDV', axis=1).values

y = boston['MEDV'].values

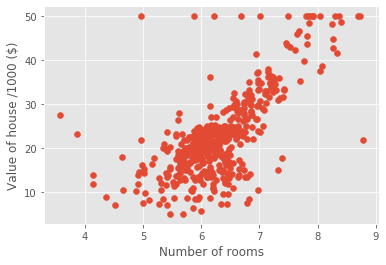

Predicting house value from a single feature

# single feature: the average num of romms in a block

X_rooms = X[:,5] # fifth column

# check type

type(X_rooms), type(y)

(numpy.ndarray, numpy.ndarray)

# Keep the first dimension, but add another dimension of size one to X,from (506,) to (506, 1)

y = y.reshape(-1, 1)

X_rooms = X_rooms.reshape(-1, 1)

X_rooms.shape

(506, 1)

Plotting house value vs. number of rooms

plt.scatter(X_rooms, y)

plt.ylabel('Value of house /1000 ($)')

plt.xlabel('Number of rooms')

plt.show();

# more rooms leads to higher prices

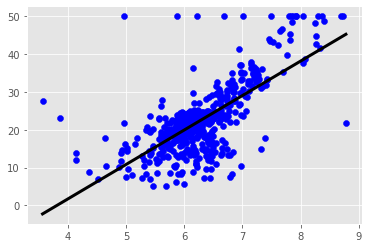

Fitting a regression model

import numpy as np

from sklearn.linear_model import LinearRegression

# instantiate LinearRegression as reg

reg = LinearRegression()

# fit regressor to the data

reg.fit(X_rooms, y)

# check out the regressors predictions over the range of the data by using np.linspace between the maximum

# and minimum number of rooms and make prediction for this data

prediction_space = np.linspace(min(X_rooms),

max(X_rooms)).reshape(-1, 1)

plt.scatter(X_rooms, y, color='blue')

plt.plot(prediction_space, reg.predict(prediction_space),

color='black', linewidth=3)

plt.show()

The basics of linear regression

Regression mechanics

- y = ax + b

- x = single feature

-

a, b = parameters of model

- How do we choose a and b?

- Define an error functions for any given line

- Choose the line that minimizes the error function

The loss function

Ordinary least squares(OLS): Minimize sum of squares of residuals

Linear regression in higher dimensions

$y = a_1x_1 +a_2x_2 + b$

- To fit a linear regression model here:

- Need to specify 3 variables

- In higher dimensions:

- Must specify coefficient for each feature and the variable b

$y = a_1x_1 +a_2x_2 + a_3x_3+ \dots +a_nx_n +b$

- Must specify coefficient for each feature and the variable b

- Scikit-learn API works exactly the same way:

- Pass two arrays: Features, and target

Linear regression on all features

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from sklearn.linear_model import LinearRegression

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size = 0.3, random_state=42)

reg_all = LinearRegression()

reg_all.fit(X_train, y_train)

y_pred = reg_all.predict(X_test)

reg_all.score(X_test, y_test)

0.711226005748496

Cross-validation

Cross-validation is a vital step in evaluating a model. It maximizes the amount of data that is used to train the model, as during the course of training, the model is not only trained, but also tested on all of the available data.

Cross-validation motivation

- Model performance is dependent on way the data is split

- Not representative of the model’s ability to generalize

- Solution: Cross-validation!

Cross-validation and model performance

- Cross-validation and model performance

- 10 folds = 10-fold CV

- k folds = k-fold CV

- More folds = More computationally expensive

Cross-validation in scikit-learn

from sklearn.model_selection import cross_val_score

from sklearn.linear_model import LinearRegression

# instantiate model

reg = LinearRegression()

# call cross val score with the regressor, the feature data and the target data as the first three positional argument

# specify the numver of fold with cv

cv_results = cross_val_score(reg, X, y, cv=5)

# the length of the array is the number of folds utilized

# note that the score reported is R square(default score for linear regression)

print(cv_results)

[ 0.63919994 0.71386698 0.58702344 0.07923081 -0.25294154]

np.mean(cv_results)

0.3532759243958772

Regularized regression

Linear least squares, Lasso,ridge regression有何本质区别?

Why regularize?

- Recall: Linear regression minimizes a loss function

- It chooses a coefficient for each feature variable

- Large coefficients can lead to overfitting

- Penalizing large coefficients: Regularization

Ridge regression

- Loss function = OLS loss function + $\alpha * \sum_{i=1}^n \alpha_i^2$

- Alpha: Parameter we need to choose

- Picking alpha here is similar to picking k in k-NN

- Hyperparameter tuning (More in Chapter 3)

- Alpha controls model complexity

- Alpha = 0: We get back OLS (Can lead to overfitting)

- Very high alpha: Can lead to underfitting

from sklearn.linear_model import Ridge

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size = 0.3, random_state=42)

# set up alpha, normalize insure all the variables are on the same scale

ridge = Ridge(alpha=0.1, normalize=True)

ridge.fit(X_train, y_train)

ridge_pred = ridge.predict(X_test)

ridge.score(X_test, y_test)

0.6996938275127313

Lasso regression

-

Loss function = OLS loss function + $\alpha * \sum_{i=1}^n \alpha_i $

from sklearn.linear_model import Lasso

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y,

test_size = 0.3, random_state=42)

lasso = Lasso(alpha=0.1, normalize=True)

# Fit the regressor to the data

lasso.fit(X_train, y_train)

lasso_pred = lasso.predict(X_test)

lasso.score(X_test, y_test)

0.5950229535328551

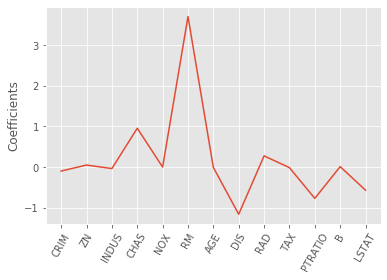

Lasso regression for feature selection

- Can be used to select important features of a dataset

- Shrinks the coefficients of less important features to exactly 0

from sklearn.linear_model import Lasso

names = boston.drop('MEDV', axis=1).columns

lasso = Lasso(alpha=0.1)

# Compute and print the coefficients,extract the coef attribute and store in lasso coef

lasso_coef = lasso.fit(X, y).coef_

# plotting the coefficients as a function of feature name

_ = plt.plot(range(len(names)), lasso_coef)

_ = plt.xticks(range(len(names)), names, rotation=60)

_ = plt.ylabel('Coefficients')

plt.show()

# Lasso selected out the 'RM' feature as being the most important for predicting

# Boston house prices, while shrinking the coefficients of certain other features to 0.

Fine-tuning your model

How good is your model?

Classification metrics

- Measuring model performance with accuracy:

- Fraction of correctly classified samples

- Not always a useful metric

Class imbalance example: Emails

- Spam classification

- 99% of emails are real; 1% of emails are spam

- Could build a classifier that predicts ALL emails as real

- 99% accurate!

- But horrible at actually classifying spam

- Fails at its original purpose

- Need more nuanced metrics

Diagnosing classification predictions

- Confusion matrix

| Predicted: Spam Email | Predicted: Real Email | |

|---|---|---|

| Actual: Spam Email | True Positive | False Negative |

| Actual: Real Email | False Positive | True Negative |

Metrics from the confusion matrix

-

Accuracy:$\frac{tp+tn}{tp+tn+fp+fn}$

-

Precision:$\frac{tp}{tp+fp}$

-

Recall: $\frac{tp}{tp+fn}$

-

F1score: $2* \frac{Precision* Recall}{Precisio+Recall}$

-

High precision: Not many real emails predicted as spam

-

High recall: Predicted most spam emails correctly

iris = datasets.load_iris()

X = iris.data

y = iris.target

df = pd.DataFrame(X, columns=iris.feature_names)

# Import necessary modules

from sklearn.metrics import classification_report

from sklearn.metrics import confusion_matrix

# Instantiate a k-NN classifier: knn

knn = KNeighborsClassifier(n_neighbors=8)

# Create training and test set

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y,

test_size=0.4, random_state=42)

# Fit the classifier to the training data

knn.fit(X_train, y_train)

# Predict the labels of the test data: y_pred

y_pred = knn.predict(X_test)

# compute confusion matrix

print(confusion_matrix(y_test, y_pred))

[[23 0 0]

[ 0 19 0]

[ 0 1 17]]

# compute result matrix

print(classification_report(y_test, y_pred))

precision recall f1-score support

0 1.00 1.00 1.00 23

1 0.95 1.00 0.97 19

2 1.00 0.94 0.97 18

accuracy 0.98 60

macro avg 0.98 0.98 0.98 60

weighted avg 0.98 0.98 0.98 60

Logistic regression and the ROC curve

Logistic regression for binary classification

- Logistic regression outputs probabilities

- If the probability ‘p’ is greater than 0.5:

- The data is labeled ‘1’

- If the probability ‘p’ is less than 0.5:

- The data is labeled ‘0’

from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegression

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

import warnings

warnings.filterwarnings("ignore", category=FutureWarning)

logreg = LogisticRegression()

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size=0.4, random_state=42)

logreg.fit(X_train, y_train)

y_pred = logreg.predict(X_test)

Probability thresholds

- By default, logistic regression threshold = 0.5

- Not specific to logistic regression

- k-NN classifiers also have thresholds

- What happens if we vary the threshold?

Exercise

Building a logistic regression model

Time to build your first logistic regression model! scikit-learn makes it very easy to try different models, since the Train-Test-Split/Instantiate/Fit/Predict paradigm applies to all classifiers and regressors - which are known in scikit-learn as ‘estimators’. You’ll see this now for yourself as you train a logistic regression model on exactly the same data as in the previous exercise. Will it outperform k-NN? There’s only one way to find out!

diabetes = pd.read_csv("data/diabetes.csv")

X = diabetes.drop('diabetes', axis=1).values

y = diabetes['diabetes'].values

# Import the necessary modules

from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegression

from sklearn.metrics import confusion_matrix, classification_report

# Create training and test sets

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size = 0.4, random_state=42)

# Create the classifier: logreg

logreg = LogisticRegression()

# Fit the classifier to the training data

logreg.fit(X_train, y_train)

# Predict the labels of the test set: y_pred

y_pred = logreg.predict(X_test)

# Compute and print the confusion matrix and classification report

print(confusion_matrix(y_test, y_pred))

print(classification_report(y_test, y_pred))

[[174 32]

[ 36 66]]

precision recall f1-score support

0 0.83 0.84 0.84 206

1 0.67 0.65 0.66 102

accuracy 0.78 308

macro avg 0.75 0.75 0.75 308

weighted avg 0.78 0.78 0.78 308

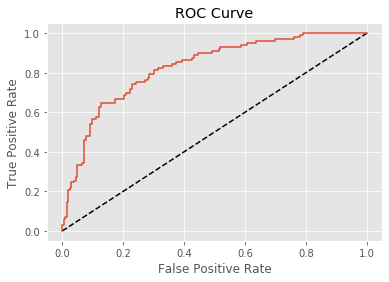

Plotting an ROC curve

Classification reports and confusion matrices are great methods to quantitatively evaluate model performance, while ROC curves provide a way to visually evaluate models. As Hugo demonstrated in the video, most classifiers in scikit-learn have a .predict_proba() method which returns the probability of a given sample being in a particular class. Having built a logistic regression model, you’ll now evaluate its performance by plotting an ROC curve. In doing so, you’ll make use of the .predict_proba() method and become familiar with its functionality.

Here, you’ll continue working with the PIMA Indians diabetes dataset. The classifier has already been fit to the training data and is available as logreg.

# Import necessary modules

from sklearn.metrics import roc_curve

# Compute predicted probabilities: y_pred_prob

y_pred_prob = logreg.predict_proba(X_test)[:,1]

# Generate ROC curve values: fpr, tpr, thresholds

fpr, tpr, thresholds = roc_curve(y_test, y_pred_prob)

# Plot ROC curve

plt.plot([0, 1], [0, 1], 'k--')

plt.plot(fpr, tpr)

plt.xlabel('False Positive Rate')

plt.ylabel('True Positive Rate')

plt.title('ROC Curve')

plt.show()

Area under the ROC curve

- Larger area under the ROC curve(AUC) = better model

Exercise

AUC computation

Say you have a binary classifier that in fact is just randomly making guesses. It would be correct approximately 50% of the time, and the resulting ROC curve would be a diagonal line in which the True Positive Rate and False Positive Rate are always equal. The Area under this ROC curve would be 0.5. This is one way in which the AUC, is an informative metric to evaluate a model. If the AUC is greater than 0.5, the model is better than random guessing. Always a good sign!

In this exercise, you’ll calculate AUC scores using the roc_auc_score() function from sklearn.metrics as well as by performing cross-validation on the diabetes dataset.

# Import necessary modules

from sklearn.metrics import roc_auc_score

from sklearn.model_selection import cross_val_score

# Compute predicted probabilities: y_pred_prob

y_pred_prob = logreg.predict_proba(X_test)[:,1]

# Compute and print AUC score

print("AUC: {}".format(roc_auc_score(y_test, y_pred_prob)))

# Compute cross-validated AUC scores: cv_auc

cv_auc = cross_val_score(logreg, X, y, cv=5, scoring='roc_auc')

# Print list of AUC scores

print("AUC scores computed using 5-fold cross-validation: {}".format(cv_auc))

AUC: 0.8268608414239482

AUC scores computed using 5-fold cross-validation: [0.7987037 0.80777778 0.81944444 0.86622642 0.85037736]

Hyperparameter tuning

- Linear regression: Choosing parameters

- Ridge/lasso regression: Choosing alpha

- k-Nearest Neighbors: Choosing n_neighbors Parameters like alpha and k: Hyperparameters

- Hyperparameters cannot be learned by fitting the model

Choosing the correct hyperparameter

- Try a bunch of different hyperparameter values Fit all of them separately

- See how well each performs

- Choose the best performing one

- It is essential to use cross-validation

GridSearchCV in scikit-learn

from sklearn.model_selection import GridSearchCV

# specify the hyperparameter as a dictionary in which the keys are the dictionary

# which the keys are the hyperparameter names, such as n_neighbors in KNN or alpha in lasso regression.

# The values in the grid dictionary are lists containing the values we wish to tune the relevant hyperparameter(s) over

# if specify multiple parameters, all possible combinations will be tried

param_grid = {'n_neighbors': np.arange(1, 50)}

# ibnstantiate classifier

knn = KNeighborsClassifier()

# pass our model(knn), the gird we wish to tune over(param_grid) and the # of folds that we wish to use

knn_cv = GridSearchCV(knn, param_grid, cv=5) # return a GridSearch object that can fit the data

# This fit performs the actual grid search inplace

knn_cv.fit(X, y)

# apply the attributes beat params, to show the hyperparameter perform the best

knn_cv.best_params_

{'n_neighbors': 14}

# apply the attributes beat score(mean cross validation score over that fold)

knn_cv.best_score_

0.7578125

Exercise

Hyperparameter tuning with GridSearchCV

Hugo demonstrated how to tune the n_neighbors parameter of the KNeighborsClassifier() using GridSearchCV on the voting dataset. You will now practice this yourself, but by using logistic regression on the diabetes dataset instead!

Like the alpha parameter of lasso and ridge regularization that you saw earlier, logistic regression also has a regularization parameter: C. C controls the inverse of the regularization strength, and this is what you will tune in this exercise. A large C can lead to an overfit model, while a small C can lead to an underfit model.

The hyperparameter space for C has been setup for you. Your job is to use GridSearchCV and logistic regression to find the optimal C in this hyperparameter space. The feature array is available as X and target variable array is available as y.

# Import necessary modules

from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegression

from sklearn.model_selection import GridSearchCV

# Setup the hyperparameter grid by using c_space as the grid of values to tune C over.

c_space = np.logspace(-5, 8, 15)

param_grid = {'C': c_space }

# Instantiate a logistic regression classifier: logreg

logreg = LogisticRegression()

# Instantiate the GridSearchCV object: logreg_cv

logreg_cv = GridSearchCV(logreg, param_grid, cv=5) # specify the classifier, parameter grid, and number of folds to use.

# Fit it to the data

logreg_cv.fit(X, y)

# Print the tuned parameters and score

print("Tuned Logistic Regression Parameters: {}".format(logreg_cv.best_params_))

print("Best score is {}".format(logreg_cv.best_score_))

Tuned Logistic Regression Parameters: {'C': 268.2695795279727}

Best score is 0.7708333333333334

Hyperparameter tuning with RandomizedSearchCV

GridSearchCV can be computationally expensive, especially if you are searching over a large hyperparameter space and dealing with multiple hyperparameters. A solution to this is to use RandomizedSearchCV, in which not all hyperparameter values are tried out. Instead, a fixed number of hyperparameter settings is sampled from specified probability distributions. You’ll practice using RandomizedSearchCV in this exercise and see how this works.

Here, you’ll also be introduced to a new model: the Decision Tree. Don’t worry about the specifics of how this model works. Just like k-NN, linear regression, and logistic regression, decision trees in scikit-learn have .fit() and .predict() methods that you can use in exactly the same way as before. Decision trees have many parameters that can be tuned, such as max_features, max_depth, and min_samples_leaf: This makes it an ideal use case for RandomizedSearchCV.

# Import necessary modules

from scipy.stats import randint

from sklearn.tree import DecisionTreeClassifier

from sklearn.model_selection import RandomizedSearchCV

# Setup the parameters and distributions to sample from: param_dist

param_dist = {"max_depth": [3, None],

"max_features": randint(1, 9),

"min_samples_leaf": randint(1, 9),

"criterion": ["gini", "entropy"]}

# Instantiate a Decision Tree classifier: tree

tree = DecisionTreeClassifier()

# Instantiate the RandomizedSearchCV object: tree_cv

tree_cv = RandomizedSearchCV(tree, param_dist, cv=5)

# Fit it to the data

tree_cv.fit(X, y)

RandomizedSearchCV(cv=5, error_score='raise-deprecating',

estimator=DecisionTreeClassifier(class_weight=None,

criterion='gini',

max_depth=None,

max_features=None,

max_leaf_nodes=None,

min_impurity_decrease=0.0,

min_impurity_split=None,

min_samples_leaf=1,

min_samples_split=2,

min_weight_fraction_leaf=0.0,

presort=False,

random_state=None,

splitter='best'),

iid='w...None,

param_distributions={'criterion': ['gini', 'entropy'],

'max_depth': [3, None],

'max_features': <scipy.stats._distn_infrastructure.rv_frozen object at 0x7f8a0b827710>,

'min_samples_leaf': <scipy.stats._distn_infrastructure.rv_frozen object at 0x7f8a0ccc1f10>},

pre_dispatch='2*n_jobs', random_state=None, refit=True,

return_train_score=False, scoring=None, verbose=0)

Note that RandomizedSearchCV will never outperform GridSearchCV. Instead, it is valuable because it saves on computation time.

Hold-out set for final evaluation

Hold-out set reasoning

- How well can the model perform on never before seen data?

- Using ALL data for cross-validation is not ideal

- Split data into training and hold-out set at the beginning

- Perform grid search cross-validation on training set

- Choose best hyperparameters and evaluate on hold-out set

Exercise

Hold-out set in practice I: Classification

You will now practice evaluating a model with tuned hyperparameters on a hold-out set. The feature array and target variable array from the diabetes dataset have been pre-loaded as X and y.

In addition to C, logistic regression has a 'penalty' hyperparameter which specifies whether to use 'l1' or 'l2' regularization. Your job in this exercise is to create a hold-out set, tune the 'C' and 'penalty' hyperparameters of a logistic regression classifier using GridSearchCV on the training set.

diabetes = pd.read_csv("data/diabetes.csv")

X = diabetes.drop('diabetes', axis=1)

y = diabetes['diabetes']

# handle missing data

# instaniate an instance of the imputer

from sklearn.preprocessing import Imputer

imp = Imputer(missing_values=0, strategy='mean', axis=0) # axis=0, impute along columns

imp.fit(X)

X = imp.transform(X) # due to their ability to transform our data as such, impters are known as transformers

X

array([[ 6. , 148. , 72. , ..., 33.6 , 0.627, 50. ],

[ 1. , 85. , 66. , ..., 26.6 , 0.351, 31. ],

[ 8. , 183. , 64. , ..., 23.3 , 0.672, 32. ],

...,

[ 5. , 121. , 72. , ..., 26.2 , 0.245, 30. ],

[ 1. , 126. , 60. , ..., 30.1 , 0.349, 47. ],

[ 1. , 93. , 70. , ..., 30.4 , 0.315, 23. ]])

# Import necessary modules

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegression

from sklearn.model_selection import GridSearchCV

import warnings

warnings.filterwarnings(action='ignore',category=DeprecationWarning)

# Create the hyperparameter grid

c_space = np.logspace(-5, 8, 15)

param_grid = {'C': c_space, 'penalty': ['l1', 'l2']}

# Instantiate the logistic regression classifier: logreg

logreg = LogisticRegression()

# Create train and test sets

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size = 0.4, random_state=42)

# Instantiate the GridSearchCV object: logreg_cv

logreg_cv = GridSearchCV(logreg, param_grid, cv=5)

# Fit it to the training data

logreg_cv.fit(X_train, y_train)

# Print the optimal parameters and best score

print("Tuned Logistic Regression Parameter: {}".format(logreg_cv.best_params_))

print("Tuned Logistic Regression Accuracy: {}".format(logreg_cv.best_score_))

Tuned Logistic Regression Parameter: {'C': 3.727593720314938, 'penalty': 'l1'}

Tuned Logistic Regression Accuracy: 0.7695652173913043

Hold-out set in practice II: Regression

Remember lasso and ridge regression from the previous chapter? Lasso used the L1 penalty to regularize, while ridge used the L2 penalty. There is another type of regularized regression known as the elastic net. In elastic net regularization, the penalty term is a linear combination of the L1 and L2 penalties:

$a∗L1+b∗L2$

In scikit-learn, this term is represented by the 'l1_ratio' parameter: An 'l1_ratio' of 1 corresponds to an L1 penalty, and anything lower is a combination of L1 and L2.

In this exercise, you will GridSearchCV to tune the 'l1_ratio' of an elastic net model trained on the Gapminder data. As in the previous exercise, use a hold-out set to evaluate your model’s performance.

# Import necessary modules

from sklearn.linear_model import ElasticNet

from sklearn.metrics import mean_squared_error

from sklearn.model_selection import GridSearchCV

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

# Create train and test sets

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size=0.4, random_state=42)

# Create the hyperparameter grid

l1_space = np.linspace(0, 1, 30)

param_grid = {'l1_ratio': l1_space}

# Instantiate the ElasticNet regressor: elastic_net

elastic_net = ElasticNet()

# Setup the GridSearchCV object: gm_cv

gm_cv = GridSearchCV(elastic_net, param_grid, cv=5)

# Fit it to the training data

gm_cv.fit(X_train, y_train)

# Predict on the test set and compute metrics

y_pred = gm_cv.predict(X_test)

r2 = gm_cv.score(X_test, y_test)

mse = mean_squared_error(y_test, y_pred)

print("Tuned ElasticNet l1 ratio: {}".format(gm_cv.best_params_))

print("Tuned ElasticNet R squared: {}".format(r2))

print("Tuned ElasticNet MSE: {}".format(mse))

Tuned ElasticNet l1 ratio: {'l1_ratio': 0.13793103448275862}

Tuned ElasticNet R squared: 0.2508917697155366

Tuned ElasticNet MSE: 0.16592450386592536

Preprocessing and pipelines

Preprocessing data

Dealing with categorical features

- Scikit-learn will not accept categorical features by default

- Need to encode categorical features numerically

- Convert to ‘dummy variables’

- 0: Observation was NOT that category

- 1: Observation was that category

Dealing with categorical features in Python

- scikit-learn: OneHotEncoder()

- pandas: get_dummies()

Automobile dataset

- mpg: Target Variable

- Origin: Categorical Feature

Encoding dummy variables

import pandas as pd

df = pd.read_csv('data/auto.csv')

df_origin = pd.get_dummies(df)

print(df_origin.head())

mpg displ hp weight accel size origin_Asia origin_Europe \

0 18.0 250.0 88 3139 14.5 15.0 0 0

1 9.0 304.0 193 4732 18.5 20.0 0 0

2 36.1 91.0 60 1800 16.4 10.0 1 0

3 18.5 250.0 98 3525 19.0 15.0 0 0

4 34.3 97.0 78 2188 15.8 10.0 0 1

origin_US

0 1

1 1

2 0

3 1

4 0

df_origin = df_origin.drop('origin_Asia', axis=1)

print(df_origin.head())

mpg displ hp weight accel size origin_Europe origin_US

0 18.0 250.0 88 3139 14.5 15.0 0 1

1 9.0 304.0 193 4732 18.5 20.0 0 1

2 36.1 91.0 60 1800 16.4 10.0 0 0

3 18.5 250.0 98 3525 19.0 15.0 0 1

4 34.3 97.0 78 2188 15.8 10.0 1 0

Linear regression with dummy variables

X = boston.drop('MEDV', axis=1).values

y = boston['MEDV'].values

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from sklearn.linear_model import Ridge

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size=0.3, random_state=42)

ridge = Ridge(alpha=0.5, normalize=True).fit(X_train, y_train)

ridge.score(X_test, y_test)

0.6658827571518846

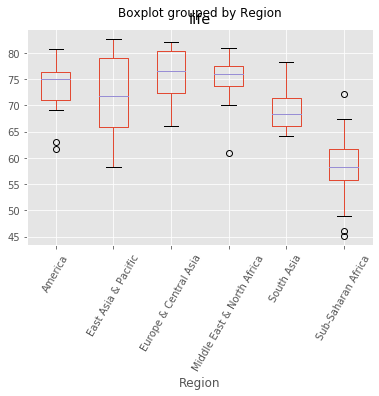

Exercise

Exploring categorical features

The Gapminder dataset that you worked with in previous chapters also contained a categorical 'Region' feature, which we dropped in previous exercises since you did not have the tools to deal with it. Now however, you do, so we have added it back in!

Your job in this exercise is to explore this feature. Boxplots are particularly useful for visualizing categorical features such as this.

# Import pandas

import pandas as pd

# Read 'gapminder.csv' into a DataFrame: df

df = pd.read_csv('data/gapminder.csv')

# Create a boxplot of life expectancy per region

df.boxplot('life', 'Region', rot=60)

# Show the plot

plt.show()

Creating dummy variables

As Andy discussed in the video, scikit-learn does not accept non-numerical features. You saw in the previous exercise that the 'Region' feature contains very useful information that can predict life expectancy. For example, Sub-Saharan Africa has a lower life expectancy compared to Europe and Central Asia. Therefore, if you are trying to predict life expectancy, it would be preferable to retain the 'Region' feature. To do this, you need to binarize it by creating dummy variables, which is what you will do in this exercise.

# Create dummy variables: df_region

df_region = pd.get_dummies(df)

# Print the columns of df_region

print(df_region.columns)

# Create dummy variables with drop_first=True: df_region

df_region = df_region.drop('Region_America', axis=1)

# or: df_region = pd.get_dummies(df, drop_first=True)

# Print the new columns of df_region

print(df_region.columns)

Index(['population', 'fertility', 'HIV', 'CO2', 'BMI_male', 'GDP',

'BMI_female', 'life', 'child_mortality', 'Region_America',

'Region_East Asia & Pacific', 'Region_Europe & Central Asia',

'Region_Middle East & North Africa', 'Region_South Asia',

'Region_Sub-Saharan Africa'],

dtype='object')

Index(['population', 'fertility', 'HIV', 'CO2', 'BMI_male', 'GDP',

'BMI_female', 'life', 'child_mortality', 'Region_East Asia & Pacific',

'Region_Europe & Central Asia', 'Region_Middle East & North Africa',

'Region_South Asia', 'Region_Sub-Saharan Africa'],

dtype='object')

Regression with categorical features

Having created the dummy variables from the 'Region' feature, you can build regression models as you did before. Here, you’ll use ridge regression to perform 5-fold cross-validation.

The feature array X and target variable array y have been pre-loaded.

# Import necessary modules

from sklearn.model_selection import cross_val_score

from sklearn.linear_model import Ridge

# Instantiate a ridge regressor: ridge

ridge = Ridge(alpha=0.5, normalize=True)

# Perform 5-fold cross-validation: ridge_cv

ridge_cv = cross_val_score(ridge, X, y, cv=5)

# Print the cross-validated scores

print(ridge_cv)

[0.66758848 0.69340446 0.47352712 0.24855188 0.29564884]

Handling missing data

PIMA Indians dataset

df = pd.read_csv('data/diabetes.csv')

df.info()

<class 'pandas.core.frame.DataFrame'>

RangeIndex: 768 entries, 0 to 767

Data columns (total 9 columns):

pregnancies 768 non-null int64

glucose 768 non-null int64

diastolic 768 non-null int64

triceps 768 non-null int64

insulin 768 non-null int64

bmi 768 non-null float64

dpf 768 non-null float64

age 768 non-null int64

diabetes 768 non-null int64

dtypes: float64(2), int64(7)

memory usage: 54.1 KB

print(df.head())

pregnancies glucose diastolic triceps insulin bmi dpf age \

0 6 148 72 35 0 33.6 0.627 50

1 1 85 66 29 0 26.6 0.351 31

2 8 183 64 0 0 23.3 0.672 32

3 1 89 66 23 94 28.1 0.167 21

4 0 137 40 35 168 43.1 2.288 33

diabetes

0 1

1 0

2 1

3 0

4 1

Dropping missing data

df.insulin.replace(0, np.nan, inplace=True)

df.triceps.replace(0, np.nan, inplace=True)

df.bmi.replace(0, np.nan, inplace=True)

df.info()

<class 'pandas.core.frame.DataFrame'>

RangeIndex: 768 entries, 0 to 767

Data columns (total 9 columns):

pregnancies 768 non-null int64

glucose 768 non-null int64

diastolic 768 non-null int64

triceps 541 non-null float64

insulin 394 non-null float64

bmi 757 non-null float64

dpf 768 non-null float64

age 768 non-null int64

diabetes 768 non-null int64

dtypes: float64(4), int64(5)

memory usage: 54.1 KB

df = df.dropna() # remove columns contain Nan

df.shape # half of rows droped, unacceptable

(393, 9)

Imputing missing data

- Making an educated guess about the missing values

- Example: Using the mean of the non-missing entries

# instaniate an instance of the imputer

from sklearn.preprocessing import Imputer

imp = Imputer(missing_values='NaN', strategy='mean', axis=0) # axis=0, impute along columns

imp.fit(X)

X = imp.transform(X) # due to their ability to transform our data as such, impters are known as transformers

Imputing within a pipeline

- Making an educated guess about the missing values

- Example: Using the mean of the non-missing entries

from sklearn.pipeline import Pipeline

from sklearn.preprocessing import Imputer

imp = Imputer(missing_values='NaN', strategy='mean', axis=0)

logreg = LogisticRegression()

# construct a list of steps in the pipeline, where each step is a 2-tuple containing the name you wish to give the relevant step and the estimator

steps = [('imputation', imp), ('logistic_regression', logreg)]

# pass the list to the pipeline constructor

pipeline = Pipeline(steps)

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size=0.3, random_state=42)

pipeline.fit(X_train, y_train.astype('int'))

y_pred = pipeline.predict(X_test)

# compute acurracy

pipeline.score(X_test, y_test.astype('int'))

0.06578947368421052

Note: in a pipeline, each step but the last must be a transformer and the last must be an estimator, such as, a classifier or a regressor

Exercise

Dropping missing data

The voting dataset from Chapter 1 contained a bunch of missing values that we dealt with for you behind the scenes. Now, it’s time for you to take care of these yourself!

The unprocessed dataset has been loaded into a DataFrame df. Explore it in the IPython Shell with the .head() method. You will see that there are certain data points labeled with a ‘?'. These denote missing values. As you saw in the video, different datasets encode missing values in different ways. Sometimes it may be a '9999', other times a 0 - real-world data can be very messy! If you’re lucky, the missing values will already be encoded as NaN. We use NaN because it is an efficient and simplified way of internally representing missing data, and it lets us take advantage of pandas methods such as .dropna() and .fillna(), as well as scikit-learn’s Imputation transformer Imputer().

In this exercise, your job is to convert the '?'s to NaNs, and then drop the rows that contain them from the DataFrame.

df = voting

# Convert '?' to NaN

df[df == '?'] = np.nan

# Print the number of NaNs

print(df.isnull().sum())

# Print shape of original DataFrame

print("Shape of Original DataFrame: {}".format(df.shape))

# Drop missing values and print shape of new DataFrame

df = df.dropna()

# Print shape of new DataFrame

print("Shape of DataFrame After Dropping All Rows with Missing Values: {}".format(df.shape))

party 0

infants 12

water 48

budget 11

physician 11

salvador 15

religious 11

satellite 14

aid 15

missile 22

immigration 7

synfuels 21

education 31

superfund 25

crime 17

duty_free_exports 28

eaa_rsa 104

dtype: int64

Shape of Original DataFrame: (435, 17)

Shape of DataFrame After Dropping All Rows with Missing Values: (232, 17)

When many values in your dataset are missing, if you drop them, you may end up throwing away valuable information along with the missing data. It’s better instead to develop an imputation strategy. This is where domain knowledge is useful, but in the absence of it, you can impute missing values with the mean or the median of the row or column that the missing value is in.

Imputing missing data in a ML Pipeline I

As you’ve come to appreciate, there are many steps to building a model, from creating training and test sets, to fitting a classifier or regressor, to tuning its parameters, to evaluating its performance on new data. Imputation can be seen as the first step of this machine learning process, the entirety of which can be viewed within the context of a pipeline. Scikit-learn provides a pipeline constructor that allows you to piece together these steps into one process and thereby simplify your workflow.

You’ll now practice setting up a pipeline with two steps: the imputation step, followed by the instantiation of a classifier. You’ve seen three classifiers in this course so far: k-NN, logistic regression, and the decision tree. You will now be introduced to a fourth one - the Support Vector Machine, or SVM. For now, do not worry about how it works under the hood. It works exactly as you would expect of the scikit-learn estimators that you have worked with previously, in that it has the same .fit() and .predict() methods as before.

df = voting

df[df == 'y'] = 1

df[df == 'n'] = 0

df[df == '?'] = "NaN"

# Import the Imputer module

from sklearn.svm import SVC

from sklearn.preprocessing import Imputer

# Setup the Imputation transformer: imp

imp = Imputer(missing_values='NaN', strategy='most_frequent', axis=0)

# Instantiate the SVC classifier: clf

clf = SVC()

# Setup the pipeline with the required steps: steps

steps = [('imputation', imp),

('SVM', clf)]

Imputing missing data in a ML Pipeline II

Having setup the steps of the pipeline in the previous exercise, you will now use it on the voting dataset to classify a Congressman’s party affiliation. What makes pipelines so incredibly useful is the simple interface that they provide. You can use the .fit() and .predict() methods on pipelines just as you did with your classifiers and regressors!

Practice this for yourself now and generate a classification report of your predictions. The steps of the pipeline have been set up for you, and the feature array X and target variable array y have been pre-loaded. Additionally, train_test_split and classification_report have been imported from sklearn.model_selection and sklearn.metrics respectively.

X = df.drop('party', axis=1)

y = df['party']

# Import necessary modules

from sklearn.preprocessing import Imputer

from sklearn.pipeline import Pipeline

from sklearn.svm import SVC

# Setup the pipeline steps: steps

steps = [('imputation', Imputer(missing_values='NaN', strategy='most_frequent', axis=0)),

('SVM', SVC())]

# Create the pipeline: pipeline

pipeline = Pipeline(steps)

# Create training and test sets

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size=0.3, random_state=42)

# Fit the pipeline to the train set

pipeline.fit(X_train, y_train)

# Predict the labels of the test set

y_pred = pipeline.predict(X_test)

# Compute metrics

print(classification_report(y_test, y_pred))

precision recall f1-score support

democrat 0.99 0.96 0.98 85

republican 0.94 0.98 0.96 46

accuracy 0.97 131

macro avg 0.96 0.97 0.97 131

weighted avg 0.97 0.97 0.97 131

Centering and scaling

Why scale your data?

- Many models use some form of distance to inform them

- Features on larger scales can unduly infiuence the model

- Example: k-NN uses distance explicitly when making predictions

- We want features to be on a similar scale

- Normalizing (or scaling and centering)

Ways to normalize your data

- Standardization: Subtract the mean and divide by variance

- All features are centered around zero and have variance one

- Can also subtract the minimum and divide by the range Minimum zero and maximum one

- Can also normalize so the data ranges from -1 to +1

- See scikit-learn docs for further details

Scaling in scikit-learn

winequality_red = pd.read_csv("data/winequality-red.csv")

winequality_red

| fixed acidity | volatile acidity | citric acid | residual sugar | chlorides | free sulfur dioxide | total sulfur dioxide | density | pH | sulphates | alcohol | quality | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 7.4 | 0.700 | 0.00 | 1.9 | 0.076 | 11.0 | 34.0 | 0.99780 | 3.51 | 0.56 | 9.4 | 5 |

| 1 | 7.8 | 0.880 | 0.00 | 2.6 | 0.098 | 25.0 | 67.0 | 0.99680 | 3.20 | 0.68 | 9.8 | 5 |

| 2 | 7.8 | 0.760 | 0.04 | 2.3 | 0.092 | 15.0 | 54.0 | 0.99700 | 3.26 | 0.65 | 9.8 | 5 |

| 3 | 11.2 | 0.280 | 0.56 | 1.9 | 0.075 | 17.0 | 60.0 | 0.99800 | 3.16 | 0.58 | 9.8 | 6 |

| 4 | 7.4 | 0.700 | 0.00 | 1.9 | 0.076 | 11.0 | 34.0 | 0.99780 | 3.51 | 0.56 | 9.4 | 5 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 1594 | 6.2 | 0.600 | 0.08 | 2.0 | 0.090 | 32.0 | 44.0 | 0.99490 | 3.45 | 0.58 | 10.5 | 5 |

| 1595 | 5.9 | 0.550 | 0.10 | 2.2 | 0.062 | 39.0 | 51.0 | 0.99512 | 3.52 | 0.76 | 11.2 | 6 |

| 1596 | 6.3 | 0.510 | 0.13 | 2.3 | 0.076 | 29.0 | 40.0 | 0.99574 | 3.42 | 0.75 | 11.0 | 6 |

| 1597 | 5.9 | 0.645 | 0.12 | 2.0 | 0.075 | 32.0 | 44.0 | 0.99547 | 3.57 | 0.71 | 10.2 | 5 |

| 1598 | 6.0 | 0.310 | 0.47 | 3.6 | 0.067 | 18.0 | 42.0 | 0.99549 | 3.39 | 0.66 | 11.0 | 6 |

1599 rows × 12 columns

print(winequality_red.describe())

fixed acidity volatile acidity citric acid residual sugar \

count 1599.000000 1599.000000 1599.000000 1599.000000

mean 8.319637 0.527821 0.270976 2.538806

std 1.741096 0.179060 0.194801 1.409928

min 4.600000 0.120000 0.000000 0.900000

25% 7.100000 0.390000 0.090000 1.900000

50% 7.900000 0.520000 0.260000 2.200000

75% 9.200000 0.640000 0.420000 2.600000

max 15.900000 1.580000 1.000000 15.500000

chlorides free sulfur dioxide total sulfur dioxide density \

count 1599.000000 1599.000000 1599.000000 1599.000000

mean 0.087467 15.874922 46.467792 0.996747

std 0.047065 10.460157 32.895324 0.001887

min 0.012000 1.000000 6.000000 0.990070

25% 0.070000 7.000000 22.000000 0.995600

50% 0.079000 14.000000 38.000000 0.996750

75% 0.090000 21.000000 62.000000 0.997835

max 0.611000 72.000000 289.000000 1.003690

pH sulphates alcohol quality

count 1599.000000 1599.000000 1599.000000 1599.000000

mean 3.311113 0.658149 10.422983 5.636023

std 0.154386 0.169507 1.065668 0.807569

min 2.740000 0.330000 8.400000 3.000000

25% 3.210000 0.550000 9.500000 5.000000

50% 3.310000 0.620000 10.200000 6.000000

75% 3.400000 0.730000 11.100000 6.000000

max 4.010000 2.000000 14.900000 8.000000

X = winequality_red.drop('quality', axis=1).values

y = winequality_red['quality'].values

y = np.where(y<5, 1, 0)

from sklearn.preprocessing import scale

X_scaled = scale(X)

np.mean(X), np.std(X)

(8.134219224515322, 16.726533979432848)

np.mean(X_scaled), np.std(X_scaled)

(2.546626531486538e-15, 1.0)

Scaling in a pipeline

from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler

steps = [('scaler', StandardScaler()),('knn', KNeighborsClassifier())]

pipeline = Pipeline(steps)

# split dartaset in training and test set

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size=0.2, random_state=21)

# fit the pipeline to training set

knn_scaled = pipeline.fit(X_train, y_train)

# predict test set

y_pred = pipeline.predict(X_test)

# compute accuracy

accuracy_score(y_test, y_pred) # 0.956

# perform KNN without scaling

knn_unscaled = KNeighborsClassifier().fit(X_train, y_train)

knn_unscaled.score(X_test, y_test) # result accurancy of 0.928, scaling did improve our model performance

0.946875

CV and scaling in a pipeline

# build pipeline

steps = [('scaler', StandardScaler()), (('knn', KNeighborsClassifier()))]

pipeline = Pipeline(steps)

# specify yhperparameter space by creating a dictionary: the keys are pipeline step name followed by a double underscore,

# followed by the hyperparameter name, the corresponding vale is a list or an array of the values to try for that

# particular hyperparameter. In this case, we are tuning only the n neighbours in the KNN model

parameters = {knn__n_neighbors: np.arange(1, 50)}

# split data into cross-validation and hold-out set

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size=0.2, random_state=21)

# perform gridsearch over the parameters in the pipeline by instantiating the GridSearchCV object

cv = GridSearchCV(pipeline, param_grid=parameters)

# fit to training data

cv.fit(X_train, y_train)

# The predict method will call predict on the estimator with the best found parameters and we do this on the hold-out set

y_pred = cv.predict(X_test)

Scaling and CV in a pipeline

print(cv.best_params_) # {'knn__n_neighbors': 41}

print(cv.score(X_test, y_test) )# 0.956

print(classification_report(y_test, y_pred))

Exercise

Centering and scaling your data

In the video, Hugo demonstrated how significantly the performance of a model can improve if the features are scaled. Note that this is not always the case: In the Congressional voting records dataset, for example, all of the features are binary. In such a situation, scaling will have minimal impact.

You will now explore scaling for yourself on a new dataset - White Wine Quality! Hugo used the Red Wine Quality dataset in the video. We have used the 'quality' feature of the wine to create a binary target variable: If 'quality' is less than 5, the target variable is 1, and otherwise, it is 0.

The DataFrame has been pre-loaded as df, along with the feature and target variable arrays X and y. Explore it in the IPython Shell. Notice how some features seem to have different units of measurement. 'density', for instance, takes values between 0.98 and 1.04, while 'total sulfur dioxide' ranges from 9 to 440. As a result, it may be worth scaling the features here. Your job in this exercise is to scale the features and compute the mean and standard deviation of the unscaled features compared to the scaled features.

winequality_white = pd.read_csv("data/winequality-white.csv")

X = winequality_white.drop('quality', axis=1).values

y = winequality_white['quality'].values

y = np.where(y<5, 0, 1)

# Import scale

from sklearn.preprocessing import scale

# Scale the features: X_scaled

X_scaled = scale(X)

# Print the mean and standard deviation of the unscaled features

print("Mean of Unscaled Features: {}".format(np.mean(X)))

print("Standard Deviation of Unscaled Features: {}".format(np.std(X)))

# Print the mean and standard deviation of the scaled features

print("Mean of Scaled Features: {}".format(np.mean(X_scaled)))

print("Standard Deviation of Scaled Features: {}".format(np.std(X_scaled)))

Mean of Unscaled Features: 18.432687072460002

Standard Deviation of Unscaled Features: 41.54494764094571

Mean of Scaled Features: 2.739937614267761e-15

Standard Deviation of Scaled Features: 0.9999999999999999

Centering and scaling in a pipeline

With regard to whether or not scaling is effective, the proof is in the pudding! See for yourself whether or not scaling the features of the White Wine Quality dataset has any impact on its performance. You will use a k-NN classifier as part of a pipeline that includes scaling, and for the purposes of comparison, a k-NN classifier trained on the unscaled data has been provided.

The feature array and target variable array have been pre-loaded as X and y. Additionally, KNeighborsClassifier and train_test_split have been imported from sklearn.neighbors and sklearn.model_selection, respectively.

# Import the necessary modules

from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler

from sklearn.pipeline import Pipeline

# Setup the pipeline steps: steps

steps = [('scaler', StandardScaler()),

('knn', KNeighborsClassifier())]

# Create the pipeline: pipeline

pipeline = Pipeline(steps)

# Create train and test sets

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size=0.3, random_state=42)

# Fit the pipeline to the training set: knn_scaled

knn_scaled = pipeline.fit(X_train, y_train)

# Instantiate and fit a k-NN classifier to the unscaled data

knn_unscaled = KNeighborsClassifier().fit(X_train, y_train)

# Compute and print metrics

print('Accuracy with Scaling: {}'.format(knn_scaled.score(X_test, y_test)))

print('Accuracy without Scaling: {}'.format(knn_unscaled.score(X_test, y_test)))

Accuracy with Scaling: 0.964625850340136

Accuracy without Scaling: 0.9666666666666667

It looks like scaling has improved model performance!

Bringing it all together I: Pipeline for classification

It is time now to piece together everything you have learned so far into a pipeline for classification! Your job in this exercise is to build a pipeline that includes scaling and hyperparameter tuning to classify wine quality.

You’ll return to using the SVM classifier you were briefly introduced to earlier in this chapter. The hyperparameters you will tune are C and gamma. C controls the regularization strength. It is analogous to the C you tuned for logistic regression in Chapter 3, while gamma controls the kernel coefficient: Do not worry about this now as it is beyond the scope of this course.

# Setup the pipeline

steps = [('scaler', StandardScaler()),

('SVM', SVC())]

pipeline = Pipeline(steps)

# Specify the hyperparameter space

# Specify the hyperparameter space using the following notation: 'step_name__parameter_name'.

# Here, the step_name is SVM, and the parameter_names are C and gamma.

parameters = {'SVM__C':[1, 10, 100],

'SVM__gamma':[0.1, 0.01]}

# Create train and test sets

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size=0.2, random_state=21)

# Instantiate the GridSearchCV object: cv

cv = GridSearchCV(pipeline, param_grid=parameters)

# Fit to the training set

cv.fit(X_train, y_train)

# Predict the labels of the test set: y_pred

y_pred = cv.predict(X_test)

# Compute and print metrics

print("Accuracy: {}".format(cv.score(X_test, y_test)))

print(classification_report(y_test, y_pred))

print("Tuned Model Parameters: {}".format(cv.best_params_))

Accuracy: 0.9693877551020408

precision recall f1-score support

0 0.43 0.10 0.17 29

1 0.97 1.00 0.98 951

accuracy 0.97 980

macro avg 0.70 0.55 0.58 980

weighted avg 0.96 0.97 0.96 980

Tuned Model Parameters: {'SVM__C': 100, 'SVM__gamma': 0.01}

Bringing it all together II: Pipeline for regression

For this final exercise, you will return to the Gapminder dataset. Guess what? Even this dataset has missing values that we dealt with for you in earlier chapters! Now, you have all the tools to take care of them yourself!

Your job is to build a pipeline that imputes the missing data, scales the features, and fits an ElasticNet to the Gapminder data. You will then tune the l1_ratio of your ElasticNet using GridSearchCV.

All the necessary modules have been imported, and the feature and target variable arrays have been pre-loaded as X and y.

# Setup the pipeline steps: steps

steps = [('imputation', Imputer(missing_values='NaN', strategy='mean', axis=0)),

('scaler', StandardScaler()),

('elasticnet', ElasticNet())]

# Create the pipeline: pipeline

pipeline = Pipeline(steps)

# Specify the hyperparameter space

# Specify the hyperparameter space for the l1 ratio using the following notation:

# 'step_name__parameter_name'. Here, the step_name is elasticnet, and the parameter_name is l1_ratio.

parameters = {'elasticnet__l1_ratio':np.linspace(0,1,30)}

# Create train and test sets

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size=0.4, random_state=42)

# Create the GridSearchCV object: gm_cv

gm_cv = GridSearchCV(pipeline, param_grid=parameters)

# Fit to the training set

gm_cv.fit(X_train, y_train)

# Compute and print the metrics

r2 = gm_cv.score(X_test, y_test)

print("Tuned ElasticNet Alpha: {}".format(gm_cv.best_params_))

print("Tuned ElasticNet R squared: {}".format(r2))

Tuned ElasticNet Alpha: {'elasticnet__l1_ratio': 0.0}

Tuned ElasticNet R squared: 0.03467831194788973